In a recent post, commenter Jeremy H. helped point out that the use of the term “public good” is grossly abused in the case of transportation. Even Nobel economists refer to roads as “important examples of production of public goods,” ( Samuelson and Nordhaus 1985: 48-49). I’d like to spend a little more time dispensing of this myth, or as I label it, an “Urban[ism] Legend.”

As Tyler Cowen wrote the entry on Public Goods at The Concise Library of Economics:

Public goods have two distinct aspects: nonexcludability and nonrivalrous consumption. “Nonexcludability” means that the cost of keeping nonpayers from enjoying the benefits of the good or service is prohibitive.

And nonrivalrous consumption means that one consumer’s use does not inhibit the consumption by others. A clear example being that when I look at a star, it doesn’t prevent others from seeing the same star.

Back when I took Microeconomics at a respectable university in preparation for grad school, I was taught that in some cases roads are public goods. We used Greg Mankiw’s book, “Principles of Economics” which states the following on page 234:

If a road is not congested, then one person’s use does not effect anyone else. In this case, use is not rival in consumption, and the road is a public good. Yet if a road is congested, then use of that road yields a negative externality. When one person drives on the road, it becomes more crowded, and other people must drive more slowly. In this case, the road is a common resource.

This explanation made sense, but I was skeptical – something didn’t sit right with me. Let’s take a closer look.

First, Mankiw uses his assertion as an example of rivalrous vs nonrivalrous consumption, while not addressing the question of excludability. Roads are easily excludable through gates or any other mechanism that could restrict access.

Furthermore, Mankiw’s assertion that an uncongested road is nonrivalrous is simply confusing rivalrousness with the fact that the road is under-utilized and/or over-supplied at certain times.

For a silly example: if the government literally manufactured mountains of marshmallows free for the taking, Mankiw would have to consider marshmallows equally as non-rivalrous and non-excludable as uncongested roads in the US. Would he then call marshmallows a public good?

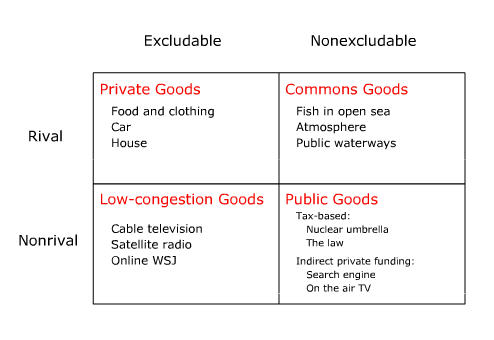

Thus we can clearly see that all roads (when done right) are neither nonrival nor non-excludable. We can use the diagram below (from Living Economics) to see that a congested (or tolled to prevent congestion) road is a private good, and in the case that a roadway is oversupplied, it is simply a “low-congestion good”, often called a “club good.”

Roads are the more commonly misused example of a public good, but we can apply the same logic to transit. First, most transit operations in the US already use a method of exclusions: the turnstyle. Second, we can see that non-rivalrousness is simply a function of over-supply in the case of the subway car that isn’t full to capacity.

As economist, Don Boudreaux puts it :

So I’m more than sympathetic to the claim that government provision of roads, bridges, and highways distorted Americans’ decisions over the years to drive and live in suburbs. But my sympathy for this claim comes from my rejection of the classic, naive case for government provision of public goods — and once that case is rejected, it cannot then be used to argue for government provision of, say, light-rail transport.

Does this alone prove that roads should be privatized? No, but the fact roads are either private goods or grossly oversupplied help weaken anyone’s case that transportation is government’s business in the first place.

I should warn you, if your Microeconomics professor teaches you this misconception unchallenged (perhaps using the Mankiw book), and gives you a true/false exam question of whether an uncongested road is a Public Good, you may want to answer “true”, or else be prepared to dispute your grade. (And feel free to send your professor a link to this post.)

Next time you catch a commenter repeating this Urban[ism] Legend (like Jeremy H. did), refer them to this post. Here are a few other links to back you up:

Are Roads Public Goods, Club Goods, Private Goods, or Common Pools? by Bruce Benson, Floria State University

Privatizing Roads by Tim Haab, “Environmental Economics” (blog)

Public Goods and Externalities: The Case of Roads by Walter Block, Loyola University

Highways Are Not (Economic) Public Goods by Rob Pitingolo, “Extraordinary Observations” (blog)

Public Goods from an Austrian Economics perspective

On the air TV isn’t non-excludable. Britain charges a television licence fee, and prosecutes non-payers

I’ve heard people essentially agree with you that roads are neither nonexcludable nor nonrival, but justify them as public goods nonetheless on a third criteria (that presumably trumps the other two) that pricing is simply too logistically difficult.

Part of this is just semantics. Most people don’t speak like economists, and the phrase “public good” means something very different. Your microeconomics professor might mark the quiz question wrong, but very few people participating in the public discourse where these decisions are being made actually use this language.

As for Don Bordeaux, his claims about the influence of highways and highway subsidy therefore undermines the case for transit subsidies misses a key point – transit and highways are not the same thing. We can lump them all together under the umbrella of ‘transportation,’ but they operate in very different ways that have key implications for his argument.

But, that doesn’t make them a public good. Or we would simply throw away

the old definition, and change the definition to “a good that is

logistically difficult to price”.

Nonetheless, I bet if that person were put in charge of a private road, they

would figure out the logistics. Maybe not 20 years ago, but in 2011, it can

be done….

Tell me more, because it doesn’t jump out at me.

Are all roads inherently excludable, or only limited-access highways (excludable by design)?

How would you implement excludability on the public street in front of my apartment? It’s a one lane city street with row homes on both sides and no off street parking.

I haven’t been to your street, but I can think of a few easy way: gates,

horses, etc…. But first I would ask you, “if you and your neighbors owned

your street, and decided to limit access, how would you go about it?” I’m

certain you could figure it out.

The equivalent of a road is not a light rail line, it would be rails themselves.

All forms of transport have three key elements – vehicles, terminals, and rights of way.

Airplanes, airports, the sky

Ships, docks, water

Cars, parking spaces, roads

Trains, train stations, tracks

From a comparison perspective, you also have to remember that transit is a service being provided. Roads are also a service to some extent (maintenance, traffic enforcement, etc) but individuals are the ones doing the driving and operating.

There is no relationship and certainly no 1:1 relationship between publicly-provided goods and public goods. From my perspective, there can be great reasons for my government to provide things which are not a public good. Simultaneously, as your chart illustrates, there are privately-provided public goods like search engines.

There is no relationship and certainly no 1:1 relationship between publicly-provided goods and public goods. From my perspective, there can be great reasons for my government to provide things which are not a public good. Simultaneously, as your chart illustrates, there are privately-provided public goods like search engines.

I’ll assume the answer to the first question is “Yes, all roads are excludable.”? And we can think out the implementation, sure. (This is much longer than I originally intended, oops!)

My street is a tiny block next to a main arterial in Philadelphia, so we even have motivation: protecting our very limited parking. The street is two-car-widths wide, one for driving, one for parking. I count 27 homes facing the block, and space for about 20 cars on the street, so things are already tight. On a Friday night, when the bars nearby pick up, things are only worse in the neighborhood.

So, let’s say everyone on the block gets together and forms a non-profit corporation, the Crown Street Authority. Motorized gates at each end, every resident gets a RFID pass for drive-through, drop-off access. Parking spaces could be auctioned off, but luckily we have 7 old ladies who don’t drive. (Just keeping things civil for now. I can’t imagine the fights if the rich yuppies on the block won all the spots because the working-class locals couldn’t put up that kind of money. Maybe we could create a more-balanced, rotating system if demand exceeds supply?)

We can’t keep the gates permanently locked though, for safety’s sake and other access. Police, fire trucks, and ambulances of course get a free pass. Everyone gets a few vouchers for visitor and handyman access, perhaps?

Now, our location blocking access between Bedford Street (a local street like ours) and Prince Avenue (the main arterial) could be a real moneymaker. But we could also sign a mutual access deal with the Bedford Street Maintenance Corporation for reciprocal drive-through rights. A network of local street authorities could be pretty self-sustaining, with mutual access deals and coordination of resources.

So far, this could work I suppose. We all pay into the CSA’s general fund. Maintenance costs would be fairly low, since it’s a small street with even lower traffic levels than currently. We’d probably get our snow plowed faster than the current situation, and I’d never come to find my (purchased or rented) parking space taken.

There are still issues and questions though:

So far we’ve only talked about cars, but the public ROW on Crown Street goes up to the front of every property line – Sidewalks are included in the public realm. Could an authority like ours purchase the pedestrian ROW too, and limit walking access to outsiders? (Or to outsiders we don’t like, to raise all sorts of civil rights issues?) Could we limit bikes, scooters, segways, and any other non-autos we deem unacceptable? Could we, and should we be able to, turn our city block into a gated community?

In a similar vein, should our powers extend to other pieces of public infrastructure in the ROW: power, gas, sewer, and so on. Would we have to purchase these lines too? Would we have to maintain them/pay the quasi-public operator ourselves to maintain them? ((Note: The public/private distinctions here aren’t so clear. In Philly, the gas company (PGW) and electirc company (PECO) are private but have a monopoly. The Water Dept (PWD) is a public agency, but is independent of the city budget as it collects its own revenues))

Conceivably, not everyone on our block might want to participate. If I don’t own a car, do I have to pay into the fund? Can I pay a lesser fee only for visitor passes? These issues can be sorted out I suppose. What if I don’t want to pay, but I go ahead and park in front of my house anyway. How would enforcement be handled? Public shaming? Calling a tow truck? Would tow companies know which calls are legitimate, and which calls are just neighborly bickering? Would law enforcement have to enforce what these block authorities decree?

Even if everyone on our block participates, what if nearby blocks don’t form corporations? They’re too lazy, or too unorganized, or just too poor to afford it? They’re unplowed, pothole-ridden streets interfere with my access to my street, but would we have to compel them to form an Authority? Or maintain a “public option” for those who opt out of doing it themselves?

None of these organizational challenges are insurmountable, but they require a lot of organization. That’s my biggest issue with this concept. We’d need very dedicated volunteers, or paid staff to maintain these arrangements. We need long sets of bylaws, and legal professionals ready to form contracts between residents and the Authority and between authorities. Like I mentioned earlier, we could conceivably pool resources among nearby authorities to be more efficient; maybe the East Philadelphia Public Works Authority could handle all local streets in our area. But at that point, why not just have the Philadelphia Streets Department do it?

Thats a great point that adds a fantastic perspective to the conversation.

However, I think I’m still missing the implication to Boudreaux’ point.

Obviously, the tracks are a private good and so are the stations and trains

to the degree they are not oversupplied. I don’t see how transit being a

service is relevant – taxis and buses are also services.

“If a road is not congested, then one person’s use does not effect anyone else”

I’m not an economist but I immediately thought of the costs of wear and tear, which definitely DO effect everyone else.

Using an empty road incurs wear which is probably a “rival” good but offset in time. For small vehicles in good weather this is (generally) negligible, but consider how durably roads must be engineered for likely boundary cases. So residential streets must be engineered to support a six-ton garbage truck, and everyone pays for this wear despite the garbage truck visiting only one morning a week. Or, more concretely: my neighbor and I pay the same to support the “public” street, despite the fact that his SUV has asphalt-shredding studded tires and my motorcycle doesn’t.

This difference is not negligible. Road engineers use a _fourth-power_ function with weight & speed to estimate wear. As a mental experiment, imagine an 8-foot wide recreational path for bikes and pedestrians, whose costs are so low that it could be built and maintained by volunteers using donated materials. If a loaded garbage truck were to drive down this “public roadway” at street speeds even a single time it would likely be destroyed, “congestion” be damned.

Bordeaux is comparing a road to a service. That’s what’s missing.

Furthermore, there are the network effects. The utility of a highway is quite limited without the vast connecting network of local roads to feed into it. A transit line is similar, but different – it is also fed by networks, but since the primary thing to be moved via a transit network is a person, the feeding network is one of sidewalks and urban areas.

What is our basic unit of transportation here? Are we aiming to move people? Goods? How are these things defined?

I guess the basic objection I have is that Bordeaux is so far into the abstract that the implications of his statement quickly fall apart when confronted with practical realities.

You thought it out very thoroughly, and brought up some great issues. I

don’t claim to have the answers of exactly what solution would be just and

what wouldn’t – it’s too complex for one person to know. In fact, if I

claimed to know the answer to such a complex problem, it would actually be a

strong case for authoritarianism.

My point is that it *could* be resolved if you and your neighbors were given

legal ownership of your street (perhaps not to everyone’s satisfaction), and

your street is thus excludable.

Exactly how privatization of streets, sidewalks, etc would happen is a

fascinating topic that I enjoy. In fact, I would speculate that many street

and most sidewalk owners would choose not to exclude people as it would harm

them more than help them based on Jane Jacobs’ theories. Nonetheless, they

would have the ability to do so.

That’s a great point and further helps diminish the case that transportation

is a public good. I would categorize phenomena like your example as an

‘externality’, just because the cause and effect between users is dispersed

and indirect.

“Nonetheless, I bet if that person were put in charge of a private road, they would figure out the logistics.”

Good gravy, YES.

The onboard electronics would be trivial: a spring scale on each axle, a speedometer, and an RFID pairing these data with an identifying token. We could get fancy and add some kind of wheel-noise monitor which would serve as a good proxy for street wear (Hey, go ahead and leave your snowchains on all year. YOU can pay for the damage!) (We could also anonymize the identifier tag to assuage privacy concerns, but really you’re already driving a vehicle with a publicly-displayed identification number past untold CCTVs so can we hang this trope up yet?)

This data would be fed to meters every [n] units/distance which is in turn tied to a network service that issues a periodic bill. This would capture nearly every external cost to driving a car on a road. The network could increase the rate at peak congestion times, which would solve the “rival goods” problem posed above, and maybe add another multiplier for extreme weather. Put a meter on the dashboard that shows you, in REAL TIME, how much your journey costs (beyond the already-privately borne costs of your car, natch). My personal bet is that capturing the engineering externalities would actually go a long way to reducing congestion, when people realize how very much cheaper small vehicles are.

As a bonus, we could eliminate truck scales.

The only reason this isn’t happening — other than the “privacy” shibboleth, above, and bear in mind that libraries solved this problem a CENTURY ago — is that people have grown accustomed to thinking of roads as free-as-in-beer goods to which they are infinitely entitled. It’s funny to watch self-proclaimed Libertarians jump all over themselves to proclaim this entirely private system impossible.

If I ever successfully privatize a road, I’m gonna hire you to run it!!!

I think about this a lot. Ever since I learned about the fourth-power rule.

I suppose my point then would be that, even though you could develop a localized road ownership system, the possibility of inefficiencies and abuses outweighs the benefits.

I wish everyone in my neighborhood was a Jane Jacobs aficianado, but that’s just too much to ask. Instead, we deal with people who don’t like newcomers, who don’t like noisy little kids playing, who don’t like noisy older kids at the bars, and sometimes of course, just don’t like people who look different. At the same, we’ve got plenty of people who think they’re the next Jane Jacobs, who want to impose their vision of a perfect neighborhood of galleries, dog parks, and avant garde street furniture. Yes, I’m being stereotypical, but I’ve been to civic association meetings, and they often feel like 95% angry old people and uppity yuppies.

These are not the folks I want managing street maintenance and parking in my neighborhood, but honestly, they are the only ones with the time and patience to do it. If everyone in the neighborhood were equally invested and equally engaged in this concept, then sure, we could effectively own our own streets. But given that we all have day jobs, we have public authorities to keep things (ostensibly) fair. I agree with you that many blocks would choose to be more open, but I wouldn’t want to allow a few dedicated folks to force a block to be more closed.

We could form larger neighborhood-sized, resident-owned road managment corporations, to save ourselves from the tyranny of volunteers, but then our costs would start to go up as we have to pay full time staff. And at that point, we’re only an order of magnitude below replicating the Streets Department. Is a resident-owned, fee-funded public works department inherently better than a public-owned, tax-funded public works department? Only if those resident owners are engaged in the management process and provide greater oversight as they currently do as voters. I see that as way too much to reasonably expect. We’d also see duplicative services in some areas (yes, even worse then this city’s current inefficiencies) and no service in other, less-organized, neighborhoods.

So, while it is possible to privatize even the smallest local roads, making a road not inherently a public good, it is sensible for us to treat local roads as public goods. It preserves fairness, without having to regulate the small back-street principalities that would be created. It allows those of us who aren’t interested in running a maintenance authority to turn over this responsibility to professionals. And it guarantees open access to the homes, businesses, and public resources in a neighborhood, fostering the density of interactions that is the great social and economic strength of cities.

Here is the economist’s answer (take it or leave it): all roads are excludable, *at some cost*. The excludability question, like all questions in economics, can only be answered at a given cost. There is no “inherent” sense to it. And furthermore, the costs of excluding will tend to *fall* over time with new technologies, which should weaken the case for government subsidization or provision. On this point generally, see: http://books.google.com/books?id=pEg2pC6entUC … but the trend is often for government to spend more on various public goods.

In defense of economics, it is not just about semantics or making good quiz questions. It is about improving efficiency in society. Of course some people might have other concerns (e.g., equity) in mind when they speak of public goods, but I would argue that in “public discourse” there often is an efficiency argument embedded, just poorly stated.

To add to Stephen’s post, another way to think of public goods is in terms of private and social benefits. The economic term “public good” means that social benefits exceed private benefits, i.e., someone other than the buyer benefits when he purchases/consumes the good. Of course, this is true of almost *any* good, but for economists the key is that public goods will be “underconsumed,” i.e., as a society we could want Y output of roads, but we only get X (where Y > X and possibly X = 0, but only the first conidition is necessary).

The rationale for government action is to supply the difference between X and Y, or encourage it in some way. Some economists and many in the “public discourse” unfortunately stop here, but one step is missing. It is only efficient for government to provide Y-X of the good if they can do it at a lower cost than Y-X, otherwise government is creating efficiences rather than eliminating them. Again, efficiency is not the only thing we care about (we might want bus lines to serve poor neighborhoods), but I’ll re-assert that this argument is embedded in most discussions, but poorly stated. Economics helps us to state it a little less poorly.

Logistically difficult is too vague. Too *costly* for the market is better. And for it to be a publicly-provided public good, we need to believe that government can overcome this logistical difficultly at a lower cost than the market. Sometimes, yes. But some things are just too costly for governments or markets to provide (given current technology), even though governments often go ahead and provide them anyway.

Logistically difficult is too vague. Too *costly* for the market is better. And for it to be a publicly-provided public good, we need to believe that government can overcome this logistical difficultly at a lower cost than the market. Sometimes, yes. But some things are just too costly for governments or markets to provide (given current technology), even though governments often go ahead and provide them anyway.

These are all valid concerns, however if control AND ownership is in the

hands of the local stakeholders, they suffer from their own follies. This

is different from the NIMBY model that ownership is common, but control in

the hands of the stakeholders, which relates to your concerns.

Basically, I’m just saying that owners will be exposed to any downsides to

their decisions, and thus would be incentivized to learn and do what works

best, which is often walkability, etc. I’m not saying mistakes wont be

made, but owners will be more keenly aware of the consequences of failure or

success of their decisions. In the end, people will locate where their

needs are best met locally, as opposed to trying to impose their ideals on

unwilling neighbors.

Someone likes neighborhoods with no kids? Fine, move to a locality that

forbids kids in it’s contractual bylaws. But don’t try to impose your

preferences via government coercion – in other words, NIMBY…

I would argue that through private ownership, people would sort out

according to their subjective preferences instead of fighting through the

public process. Will it be clean and perfect? No. Would it be better? I

think so. I admit, the transition is nearly impossible to imagine, but I

have some more refined ideas that maybe I’ll share some day.

(Also, much of the public works services could be outsourced to private

operators, which could take advantage of the economies of scale you are

concerned about. Hopefully, the higher costs of local operation would be

offset by lower taxes and better efficiency since it would no longer be a

government service.)

All great points. Better than I could say it.

[Just so he doesn’t get blamed for my amateur writing, this was not a post

that Stephen wrote. It was me (Adam) the original Market Urbanism writer

who hasn’t written as much over the past 2 years.]

Good points – I just wanted to emphasize that there’s a difference between a true difference of opinion on what is and is not a public good, versus when something is just lost in translation between the economic usage of “public good” compared to the common, much less specific usage of the phrase.

The language of economics certainly does help clean that up, but we should be clear about true misconceptions versus stuff that’s just lost in translation.

Good points. I wonder if roads might be more a case of “natural monopoly” than “public good”, in the sense that it’s more effective for a single authority/company to provide us with a ton of roads and supply us with a single charge, than to have a whole bunch of separate Street Authorities working out negotiated policies.

In one specific case, roads could be non-rival: namely, if they’re so under capacity that they can’t be congested. If existing traffic wouldn’t compromise speed even on a simple two-lane local road with at-grade intersections – for example, most urban streets – then there is no point in pricing. At low traffic levels, roads are not a continuous good, whose supply can be closely tailored to traffic; they’re can only be supplied in multiples of about 700 vehicles per direction per hour. The closest thing to a continuous supply level is if you’re in a dense urban street grid – but then there’s a very good urbanist reason to have a dense grid, even if there are no cars.

I’ll make the “natural monopoly” of roads the next Urban[ism] Legend to

debunk! Thanks for bringing it up….

Errr . . . okay. Glad to bring it to your attention, I guess.

It’s a great topic. I think the concept deserves enough of my attention to

develope a well-researched post rather than a quick comment.

this was a seriously good post! well said

For a silly example: if the government literally manufactured mountains of marshmallows free for the taking, Mankiw would have to consider marshmallows equally as non-rivalrous and non-excludable as uncongested roads in the US. Would he then call marshmallows a public good?

The marshmallows are still rival goods, because as soon as a I use a marshmallow it seriously harms everyone else’s ability to use that marshmallow, it doesn’t matter that there are plenty of other marshmallows available, that is not what makes a good rival/nonrival.

If I am driving on a local road at 4am I am not hindering anyone else’s ability to use that road also. Alon is right in that the supply function for roadway capacity is not continuous and thus we end up with over supply at some hours and undersupply at others because the supply of that limited roadway is either up to 700 cars per hour or 0 cars per hour.

The main problem is the belief that because it is possible that the government could increase the efficiency of the market in the supply of public goods, it always will. I completely agree with you that govt seems to often(almost always) oversupply roadways, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that in each and every case an efficient system would only supply enough roadways to make them rival at all times. Given traffic patterns that would imply building roadways to only handle minimum traffic level, which at 3-4am would mean having no roadways. Thus even in a more efficient system roadways would be non-rival at 3-4am.

all that analysis excludes wear and tear which as Paul points out is a type of rivalness through time. Although I believe that for the standard type roadway the average cost of wear and tear of any one vehicle trip is so insignificant as to be zero.

Your statement:

contradicts the scenario you postulate:

Because by your analysis of the marshmallow mountain, you would have to

argue that driving on that local road at 4am prevents someone else from

driving on the exact piece of pavement you are using at any given point in

time.

Further, by your definition of rivalrous according to the marshmallow

mountain analogy, nothing physical could be nonrivalrous. You could even

say that by breathing air, I am preventing someone else from simultaneously

breathing those same molecules. Thus, it would render the concept as

meaningless.

Correct. A roadway might vary between private good and club good, but it’s

never a public good.

The definition of a rival good has to do with the good being considered not how much of it there is. Then it depends on how you define the good, which I generally try do using the ways in which it is consumed. I eat a marshmallow and it then becomes unusable to anyone else. I drive along stretches of roadway at 3-4am and only cause imperceptible/infitesimal delays to my very few fellow travelers. People don’t care about being in the exact spot I am in, but in their travel speeds along the stretch of roadway.

You are right to say that if the government had built less freeway lane miles in the first place there would be fewer lengths of time in which it was non-rival.

Your distinction between club goods and public goods, depends on whether it is exludable or not, and so by saying that, you seem to agree that it is possible for roadways to be non-rival.

And something else I just noticed.

“First, Mankiw uses his assertion as an example of rivalrous vs nonrivalrous consumption, while not addressing the question of excludability.”

actually he uses the example of tolled congested freeways (private good), tolled uncongested freeways (natural monopoly), untolled congested freeways (common resource), untolled uncongested freeway (public good). At this point in time he is not making an argument about the best way to provide freeways but just that under different conditions a freeway (as built) could fall under each of the four different types of goods.

I tried to find a definition of good that would help resolve this distinction, but it’s too vague a term. Your distinction did help me realize that the marshmallow analogy could be improved upon. I should have used something that cannot not easily be apportioned, like roadways. Maybe this is a better analogy, but probably not perfect: a really, really big lollypop. I think I’ll go back and edit the post to improve the analogy. Let me know if you can think of a better analogy.

Thanks for the opportunity to improve my communication.

You lost me there. I think I made it clear that roads are excludable. Let me know what I’m missing.

Maybe you are referring to a different book by Mankiw where he contradicts himself, but page 234 of “Principles of Economics” says, “Roads can be either public goods or common resources.” Please send a link to where he makes this claim to which you are refering. Then tell me where he discusses the excludability of roads or explain how roads are not excludable.

The example of Air may clear up the confusion. In most normal situations, are is a “free good,” thus non-rival. But in others, such as a polluted city or underwater, air is now rival. So the quantity does matter when we discuss rivalry, once again not the inherent features of the good (as with cost and excludability).

This why roads can both be rival and non-rival, depending on the quantity available compared with demand. And this is also why the Marshmallow example made some sense to me (in the absurd situation where there are just stacks of marshmallows sitting around).

I am open to the notion that over-supplied roads could be considered “club goods”

Above all, and I don’t think I mentioned this before, I think you are broadly making a good point.

That is a difficulty that I have with economics coming from engineering. Common terms used in the study of economics are often ill defined. I think I would agree that a humongous lollipop,I would prefer just one honking big marshmallow, would be nonrivalrous in just the same way as overprovided freeways are. I don’t think it actually matters. The name Public Goods is a misnomer to laymen, in that it seems to imply that they should be provided by govt. Over the air radio and t.v. is a public good, and I think that very few people think the govt should provide most or all tv and radio, as opposed to defining the property rights to spectrum.

Mankiw fifth edition,

figure 1 page 226, and in the section you mention he does mention the possibility of tolls making them excludable, although he discusses this in the context of a pigovian tax and not excludability. On the Instructor’s powerpoint slides they make a bigger deal about the ability of freeways to satisfy the criteria of all four different types of goods. I never realized that he didn’t discuss all four categories as fully in the actual text of the book, and seems to contradict the claim that they could be all four types of goods.

club goods are excludable and non-rival, public goods are non-excludable and non-rival. So by categorizing roads as potentially club goods you cede the fact that they can be nonrival.

I also came from an engineering background, so I too tend to be keenly aware of the imprecision of economic terms…

Thanks for pointing that out. I stand corrected that Mankiw actually mentions excludability in roads. I guess I gave him too much credit, because, unfortunately, he is just plain wrong.

He lists toll roads as excludable, but non-toll roads as non-excludable. But just because a road is not tolled, doesn’t mean it couldn’t be tolled or access prevented.

It’s very sloppy reasoning on Mankiw’s part: to conflate “not excluded” with “not excludable” is to conflate “is” with “could be”.

I’m inclined to say yes. Particularly local streets could be club goods. But, highways are typically over-supplied private goods.

Beyond the terms used often being ill defined another common problem in Economics is a lack of precision in discussions.

I think the better way to say it is not reasonably excludable. Technically nothing is excludable.

You can exclude me from breathing air with a shot to the head, I hope everyone agrees that is unreasonable.

If I don’t pay my taxes, you could exclude me from National defense by allowing the Mexicans to come take over my house.

You can exclude me from over the air broadcast by scrambling the signal and forcing me to buy a descrambler for each station I want to watch or listen to.

With urban roadways, especially as built (say in Houston), it is only relatively recently that RFID tags and CCTV cameras have made exclusion reasonable.

I can tell you that much thought doesn’t go into changes from edition to edition, with 4->5 editions only changing the order of some chapters and the content of the little real world stories, i.e. showing inflation using Venezuela instead of Zimbabwe.

That is

Technically EVERYTHING is excludable.

Please see my comment yesterday in response to TLP. Everything is excludable *at some cost*, and the cost is related to the state of technology (as you note with RFID). Any good economist will define it this way. See the Cowen quotation in original post: he uses the word “prohibitive,” meaning “cost prohibitive.”

The pertinent questions are whether: a) it is currently cost prohibitive for *the market* to provide the good, exclude, and still earn a profit; and b) *government* can provide the good at a cost that is less than the difference between private and social benefits. Just because A is true does not imply that B is true.

Here is a quotation from Cowen and Tabarrok’s new principles text (same Cowen as above, who I consider to be a good economist, because he talks about *cost*):

“When a person cannot be CHEAPLY prevented from using a good, economists say the good is nonexcludable.” (CAPS added by me)

Of course, “how cheap is cheap?” you may ask. Well this is just a principles textbook, to introduce students to the concept. More advanced (good) texts will delve into those details. I’m not sure if Mankiw brings the notion of cost into his public goods discussion (don’t have it in front of me), but my guess is he probably does. And if not he is being sloppy and therefore just an “okay” economist in my book, not a “good” one.

I would argue that the inventions of fences, gates, barricades, and horses

made exclusion on roads reasonable. But “reasonable” is not objective

enough that we could all agree, so I’m willing to accept that a huge gray

area exists. (“precision of discussions”)

Plus, governments typically already attempt to exclude people/cars from the

roads who are not licensed.

Thanks for the link to “Privatizing Roads”, found it very interesting to read.

Is mobility the good provided by a road? It is if you think of the users as the people who move around on it. But if you think of the users as landowners nearby, then the good provided by the road is property value (in the form of access to markets, access to customers, etc.) If you assume that people are able to park and walk to anywhere that is near the road, then the land value boost is neither excludable nor rivalrous. (If you assume that the only way for people to get from the road to a piece of land is to use a driveway, then it is definitely excludable – Chuck Marohn is always telling us about those costs involved in allowing an extra driveway on a “stroad”.)

MarketUrbanism, it seems like you’re suggesting simply turning the city streets department into a private business. Sounds simpler than TLP’s proposal.

Another solution: property owners must maintain the piece of road in front of their property, up to the middle line.

This is how Meditterranean cities did it in the past, and it worked. If I remember correctly stores in Japan must clean the sidewalk in front of their store.

This might be an even better way of implementing the free market on roads because the people most affected are directly in charge, rather than having to go through a private corporation.