In most of my discussions of Houston here on the blog, I have always been quick to hedge that the city still subsidizes a system of quasi-private deed restrictions that control land use and that this is a bad thing. After reading Bernard Siegan’s sleeper market urbanist classic, “Land Use Without Zoning,” I am less sure of this position. Toward this end, I’d like to argue a somewhat contrarian case: subsidizing private deed restrictions, as is the case in Houston, is a good idea insomuch as it defrays resident demand for more restrictive citywide land-use controls.

For those of you who haven’t read my last four or five wonky blog posts on land-use regulations in Houston (what else could you possibly be doing?), here is a quick refresher. Houston doesn’t have conventional Euclidean zoning. Residents voted it down three times. However, Houston does have standard subdivision and setback controls, which serve to reduce densities. The city also enforces high minimum parking requirements outside of downtown.

On top of these standard land-use regulations, the city heavily relies on private deed restrictions. Also known as restrictive covenants, these are essentially legal agreements among neighbors about how they can and cannot use their property, often set up by a developer and signed onto as a condition for buying a home in a particular neighborhood. In most cities, deed restrictions cover superfluous lifestyle preferences not already covered by zoning, including lawn maintenance and permitted architectural styles. In Houston, however, these perform most of the functions normally covered by zoning, regulating issues such as permissible land uses, minimum lot sizes, and densities.

Houston’s deed restrictions are also different in that they are heavily subsidized by the city. In most cities, deed restrictions are overseen and enforced by parties to a deed, typically organized as a homeowners association (HOA) to which members are required to pay dues. When a resident in a subdivision breaks the rules of the deed, the HOA takes them to court on their own dime. In Houston, however, the municipal government covers the cost of enforcement, much like with zoning. Neighbors complain, the city reviews the complaint, sends the offending party a letter, and eventually takes her to court if her noncompliance continues.

This has at least three effects: First, this encourages the creation of overly detailed and broad deed restrictions, which might otherwise be a hassle to oversee and enforce if all the costs were falling on residents. Second, this leads to consistent enforcement of all rule violations, even in minor cases where residents might otherwise agree to let harmless violations that aren’t worth enforcing slide. Third, following on this second effect, this preserves the legal force of deed restrictions far beyond what might otherwise occur. If so many violations go unenforced, eventually courts stop enforcing certain rules or enforcing the rules in certain parts of the subdivision. This gradual withering away of deed restrictions is still somewhat common in Houston, indicating that many violations aren’t even worth the phone call to the city to complain, but it is less common under a system of municipal enforcement.

Houston further subsidizes deed restrictions in at least two other ways: First, the city will not issue permits for developments and improvements that run afoul of any deed restrictions. Second, Texas state law allows deed restrictions in unzoned cities (e.g. Houston) to be created, extended, or renewed with a simple majority of residents in a subdivision and they can be modified with the support of three quarters of residents. In every other state, unanimity among the affected parties is required to create, renew, or modify a deed restriction, as with most other contracts. Similar to enforcement, this acts as a kind of subsidy, making it much easier for subdivision majorities to adopt and maintain deed restrictions, meaning that Houston probably has far more active deed restrictions than one might find under regular conditions.

All of this might sound bad to you, and with good reason. Why should majorities be able to strip minorities of their property rights? Doesn’t this lead to an arbitrary patchwork of regulations, undermining comprehensive planning? Why should the city pick up the tab to enforce the preferences of middle- and upper-class homeowners?

Indeed, these are all issues under a system of subsidized deed restrictions. Yet each of these issues are far more challenging under conventional land-use regulations. Under deed restrictions, residents only have the power to downzone their immediate subdivision. Outsiders have no say in the matter, but at the same time, many residential areas, and virtually all commercial and industrial areas, are almost completely unaffected. This is in contrast to conventional land-use regulation, where active minority interest groups (i.e. homeowners) can and do capture the process and dictate the property rights of entire cities.[1] Under conventional land-use regulations, these groups nearly always decide the zoning of their local neighborhood, which can often be in conflict with regional housing or mobility planning. Again, the city then picks up the tab and enforces these preferences citywide using public resources. At most, Houston’s private deed restrictions only affect 25 percent of the city.

Yet my argument isn’t simply that deed restrictions are less bad than conventional land-use regulation. You can find that argument here. Rather, my point is that subsidized deed restrictions perform a useful political function: they give those residents with the strongest preferences for restrictions the restrictions they crave, thereby obviating the need to agitate for restrictive land-use regulations. The “homevoters” who drive land-use and zoning policy are essentially allowed to opt out of the laissez faire status quo, with some support from the city. This allows Houston to avoid having to adopt citywide conventional land-use regulations for things like land use and densities, as has happened in every other major city.

There is substantial evidence for this from Houston’s history. Consider the failed 1939 zoning push. According to Siegan, the most enthusiastic support for zoning came from Montrose, whose covenants had expired in 1936, leaving the neighborhood open to then-unwanted commercial and multifamily development. At the time, there was no city enforcement of covenants and renewal or extension often required unanimous support. This is an important point to state plainly: When their deed restrictions expired, residents started agitating for citywide zoning.

This exact same plot unfolded surrounding the failed 1948 and 1962 zoning referenda. In 1955, the deed restriction for River Oaks—an affluent white neighborhood—were set to expire after their original 30 years run (they began in 1926), after which renewal would be required every 10 years. It won’t surprise you to learn that the city’s elites, who disproportionately lived in River Oaks, became enthusiastic supporters of zoning in Houston around this time. In both referenda, River Oaks was the source of zoning support. In fact, in 1962, it was one of only two neighborhoods that voted for zoning. Again, when their deed restrictions were threatened, homeowners started agitating for zoning.

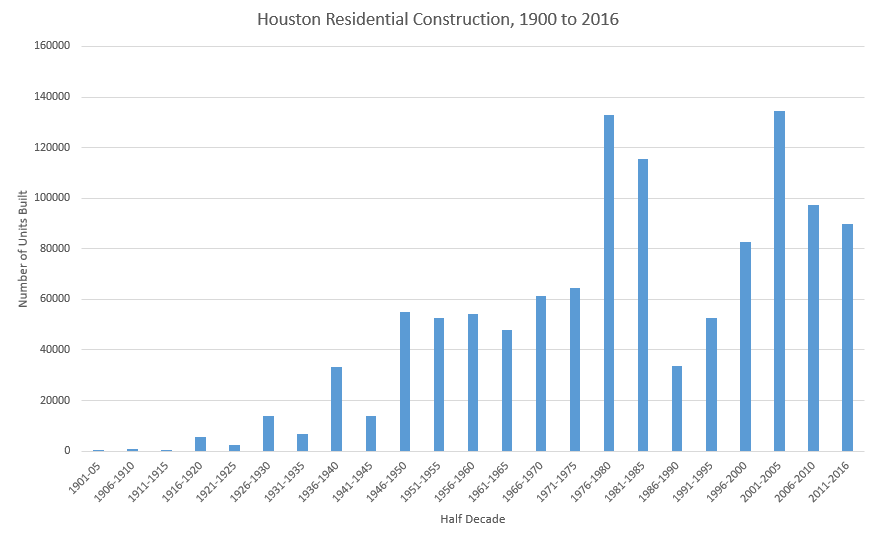

Data from the Harris County Appraisal District

There is some evidence that the same phenomenon occurred with the 1993 referendum. As you can see in Chart 1, there was a massive residential subdivision building boom in the mid- to late-1970s. Assuming for our purposes that a standard share of these developments were subject to deed restrictions, and that these deed restrictions had a standard initial run of 30 years, these deed restrictions were poised to start expiring between 2005 and 2010.[2] If we take all this together, we would expect a zoning referendum somewhere between 1995 and 2000, with deed expirations on the horizon. Lo and behold, one arrived two years early in 1993. The narrative again comes into focus: when deed restrictions are at risk, homeowners start agitating for zoning.[3]

The natural takeaway is that if you want to avoid restrictive land-use regulations, the city should actively support deed restrictions. That is to say, you must provide an effective and inexpensive way for those with the strongest preferences for strict regulations to “opt out” of the lightly regulated status quo. When you do that, you take away their incentive to lobby for conventional land-use regulations.

Houston history indicates that I am not the first person to figure this out. A mere three years after the failed 1962 zoning referendum, the Texas state legislature changed the law to allow Houston to enforce private deed restrictions and lowered the barriers to creating, renewing, and modifying them, which we discussed above. That is to say, they created an “opt out” option. After four decades of constant agitation for zoning beginning in the 1920s, there wouldn’t be a major push after 1962 for three decades. Within a decade of the 1993 referendum, the city of Houston again scaled up the enforcement of private deed restrictions in 2003, broadening enforcement to include things like design and maintenance rules.

This general policy of allowing NIMBY residents to “opt out” of liberalization isn’t just limited to preserving the non-zoning status quo. It also makes easing up on existing restrictions easier. In 1998, Houston policymakers substantially lowered minimum lot sizes from 5,000 to 1,400 square feet within the I-610 loop.[4] This constituted the most dramatic liberalization of subdivision rules in any U.S. city to date.

How was this possible? Because everyone who might have preferred a larger minimum lot size either was either already shielded from the change by deed restrictions or could easily “opt out” of the new rules. At the same time that Houston lowered minimum lot sizes, they created a process whereby a majority of local residents could petition to set higher minimum lot size rules based on the prevailing lot dimensions within their local block or neighborhood. Residents with a strong preference for large minimum lot sizes had no reason to go out and raise hell about the city as a whole, as their community was protected in proportion to the preferences of local residents.

As with deed restrictions, these local minimum lot sizes are still even less restrictive than conventional land-use regulations. Not only do they only affect a limited area and require a majority vote; they also automatically expire after 40 years. Predictably, when the city expanded these newer, more liberal subdivision rules to the city as a whole in 2013 (i.e. beyond the I-610 loop), they also lowered the threshold for adopting higher local minimum lot sizes.

Is a system of subsidized private deed restrictions and “opt out” provisions the ideal policy arrangement? No. Like zoning, they can create a messy patchwork of rules and regulations for which, as far as I’m aware, there is still no public database. But we aren’t operating in the realm of ideal policy. We are operating subject to very real political constraints, namely a vocal and powerful special interest group (i.e. homeowners) that desires strict land-use regulations around their home.

This is the genius of Houston’s unique system: Let those with strong preferences for tight restrictions have them and the city as a whole can go on operating under a largely liberal land-use regime. There is a valuable lesson here for other cities: when attempting to liberalize land-use regulations, consider strengthening the private (subdivision deed restrictions) and public (stricter local rules subject to local consensus) mechanisms whereby the most powerful opponents of liberalization can simply opt out. Houston figured this out in 1965 and again deployed this strategy to great effect in the 1998 subdivision regulation overhaul. In relationships as in city planning, sometimes you have to give a little to get a little.

For future content and discussion, follow me on Twitter at @mnolangray.

[1] Refer to Bill Fischel’s “The Homevoter Hypothesis” (2001) and associated papers, which convincingly argue that middle- and upper-class homeowners play an outsized role in determining zoning and land-use policy, particularly in smaller municipalities.

[2] These are standard assumptions about length based on Houston history. Note that this expiration length maps onto the length of a standard mortgage. As you might have guessed, FHA and private sector underwriters were major boosters of deed restrictions, as a way to secure property values in the face of non-zoning.

[3] If my theory is valid, expect a fourth zoning referendum somewhere between 2020 and 2026, 20 years after the 2000 to 2006 building boom.

[4] The causes and effects of this liberalization are the topic of a forthcoming paper. Stay tuned!