Everybody loves missing middle housing! What’s not to like? It consists of neighborly, often attractive homes that fit in equally well in Rumford, Maine, and Queens, New York. Missing middle housing types have character and personality. They’re often affordable and vintage.

Daniel Parolek’s new book Missing Middle Housing expounds the concept (which he coined), collecting in one place the arguments for missing middle housing, many examples, and several emblematic case studies. The entire book is beautifully illustrated and enjoyable to read, despite its ample technical details.

Missing Middle Housing is targeted to people who know how to read a pro forma and a zoning code. But there’s interest beyond the home-building industry. Several states and cities have rewritten codes to encourage middle housing. Portland’s RIP draws heavily on Parolek’s ideas. In Maryland, I testified warmly about the benefits of middle housing.

I came to Missing Middle Housing with very favorable views of missing middle housing. Now I’m not so sure. Parolek’s case for middle housing relies so much on aesthetics and regulation that it makes me wonder whether middle housing deserves all the love it’s currently getting from the YIMBY movement.

Can middle housing compete?

Throughout the book, Parolek makes the case that missing middle construction cannot compete, financially, with either single-family or multifamily construction. That’s quite contrary to what I’ve read elsewhere. In a chapter called “The Missing Middle Housing Affordability Solution”, Daniel Parolek and chapter co-author Karen Parolek write:

The economic benefits of Missing Middle Housing are only possible in areas where land is not already zoned for large, multiunit buildings, which will drive land prices up to the point that Missing Middle Housing will not be economically viable.

(p. 56)

On page 81, we learn,

It’s a fact that building larger buildings, say a 125-150 unit apartment or condo building, provides easier-to-identify and often larger cost efficiencies than building a four-, eight-, or even a sixteen-unit building or series of these buildings. “Overall, a 50-unit project requires about the same amount of development work to execute as a 150-unit project, but the margins are lower, and the cap rates/valuations are also generally lower,” says Curt Gunsbury, owner of Solhem Companies.

These disadvantages, relative to large multifamily developments, sound structural: there are fixed costs in land and process that have to be divided among all the units. Buyers would have to pay too much more, per unit, to make middle housing pencil out in a place where dense multifamily is also viable.

Laying out the nuts and bolts of his favored typologies, Parolek notes,

In areas of high property values, you may need to set a maximum FAR [floor area ratio] for single-family homes that is lower than FAR allowed for a duplex so the economics of a duplex can compete with them.

(p. 103)

There are good reasons to allow multi-unit buildings to be larger – but Parolek’s reason is that, pound for pound, the market prefers single family houses. This is awfully damning. It implies that missing middle housing is affordable because people don’t want it very much.

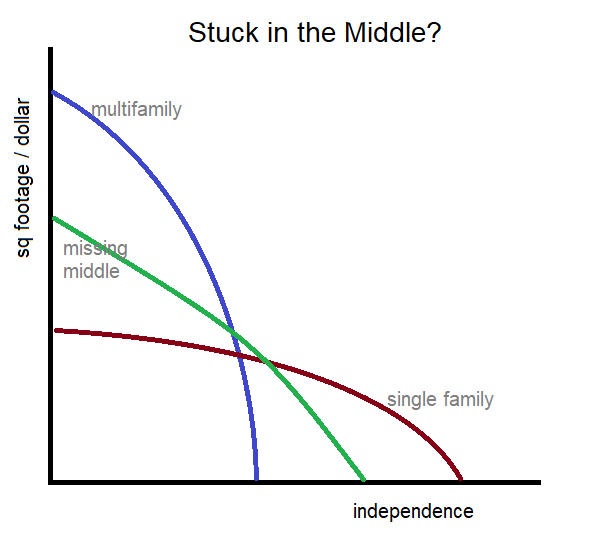

I hope that Parolek is wrong – but it’s possible that his experience is showing that his favored typologies are actually stuck in the middle. The figure below is a production possibilities frontier sketch, something you may remember from college econ. Suppose there are two main features that people like in housing (independence and square footage per dollar spent) and three ways to build housing. Single-family construction is efficient at providing independence but not much square footage. Multifamily construction, with its economies of scale, efficiently provides square footage but with little independence. Missing middle housing is more balanced, which sounds great.

But what if being balanced just means it’s rarely the best option?

In the sketch above, missing middle housing is at the “frontier” for only a short stretch, and only for buyers who demand a very precise balance between square footage and independence. Most buyers will be happier with housing built using one of the other technologies. Parolek seems to concede this with his arguments in favor of regulations intended to constrain single- and multi-family construction.

Back of the envelope

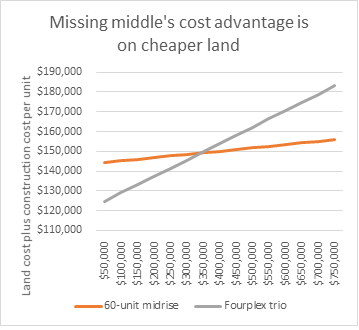

A stated advantage of missing middle housing is that it economizes on land (relative to single family) but uses low-cost construction techniques. According to the RS Means prices (for DC in 2012) that Payton Chung published in a helpful 2014 article, Type V construction (as in single-family homes and small missing middle typologies) is 16 percent cheaper per square foot than Type III construction, which is commonly used to build mid-rise buildings.

Inspired by a cool development proposal in my own neighborhood, I put together a quick calculator. Consider a developer is looking at a 15,000 square foot city lot with zero parking requirements. She can, by right, build a 60-unit apartment building with units averaging 800 square feet or subdivide into three lots and build a fourplex on each. Per Parolek, this would be a relatively dense form of missing middle. The fourplexes cost $137 per square foot to built; the midrise building costs $163.

Missing middle has an obvious construction cost advantage. But it has two disadvantages. First, it produces fewer units, so the project’s total impact on housing supply is much lower.

Second, land costs per unit are five times larger in the fourplex option, a decided disadvantage. As the graph shows, the break-even point for the developer is when the land costs $344,000 – which translates (coincidentally) to a million dollars per acre.

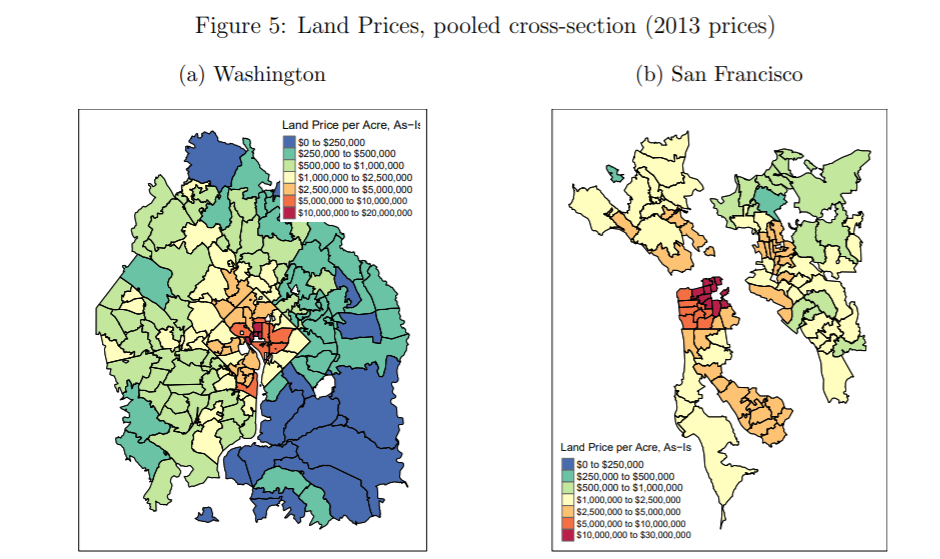

Where does land cost at least a million dollars per acre? Morris Davis et al calculated residential land prices across the U.S. They mapped two metro areas in the following figure. Of course, land prices are held down by zoning in many places where denser uses would command much higher land prices. Around DC, land costs fall below $1 million per acre in Prince George’s County and areas that are largely reserved for single-family zoning. In the Bay Area, land costs are below $1 million per acre only in Contra Costa County and a few other East Bay Zip codes.

Nationally, of course, land prices are much lower. In many small cities, missing middle construction should, if other barriers do not interfere, pencil out better than mid-rise apartments, especially if consumers are willing to pay more per square foot. However, Parolek’s pessimism about the economic viability of his own favored style has made me substantially less optimistic about its potential impact.