For a reading group, I recently read two papers about the costs and (in)efficiencies around land assembly. One advocated nudging small landowners into land assembly; the other is an implicit caution against doing so.

Graduated Density Zoning

Although he’s mostly known for parking research and policy, Donald Shoup responded to the ugliness of eminent domain in Kelo v. City of New London, with a 2008 paper suggesting “graduated density zoning” as a milder alternative. Graduated density zoning would allow greater densities or higher height limits for larger parcels – so that holdouts would face greater risk.

Samurai to Skyscrapers

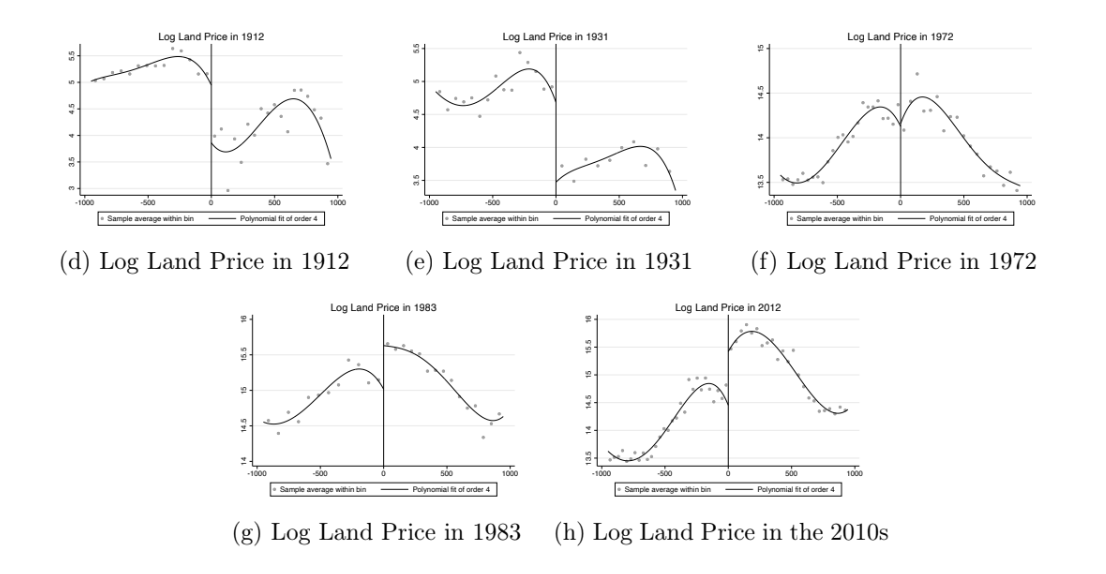

Junichi Yamasaki, Kentaro Nakajima, and Kensuke Teshima’s paper, From Samurai to Skyscrapers: How Transaction Costs Shape Tokyo, is a fascinating and technical account of how sweeping changes put the relative prices of different-sized lots on a roller-coaster from the 19th century to the present. First, large estates were mandated as a way for the shogun to keep nobles under his close control. Then, with the Meiji Restoration, the nobles were released to sell their land, swamping the market and depressing prices. The value of land in former estate areas stayed low into the 1950s.

But with the advent of skyscrapers – which need large base areas – the old estate areas first matched and then exceeded neighboring small-lot areas in central Tokyo.

A meta-lesson from this reversal is that “efficiency” is a time-bound concept. One can imagine a 1931 urban planner imposing a tight street grid and forcing lot subdivision to unlock value on the depressed side of the tracks. That didn’t happen; instead, the large lots were a land bank that allowed a skyscraper boom right near the heart of a very old city, helping propel the Japanese economy beyond middle-income status.

We should take a long, uncertain view of all “efficiencies”. Instead of just optimizing under current conditions, imagine a range of conditions. Does a proposed policy improve life under most of those? Or are we better off with some apparent inefficiencies and redundancies that might have extremely high value in some states of the world?

Back to graduated density

With Tokyo as an inspiration for cautious policymaking, let’s turn back to Shoup’s idea. In Shoup’s telling, the reason that the government would value pushing the landowner to sell is that there are technical reasons (such as skyscraper footprint requirements) why small lots cannot achieve such high efficiency. Larger lots, bigger pie.

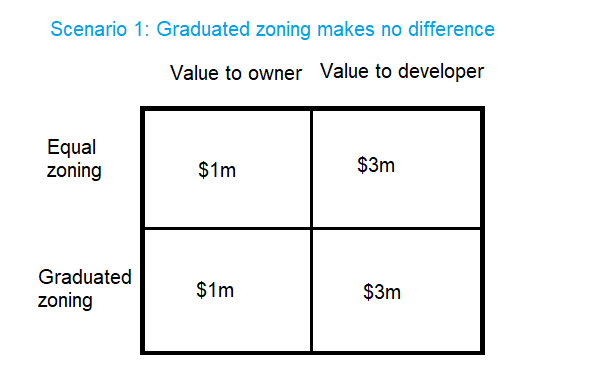

But if that’s the case – if small lots could not physically take advantage of the higher density or height limit available to large lots – then graduated density doesn’t change the game, as in Scenario 1 below.

Land assembly cases involve bargaining: if assembly can create $2 million, who gets that value? If either the owner or developer demand all of it, the other will walk away.

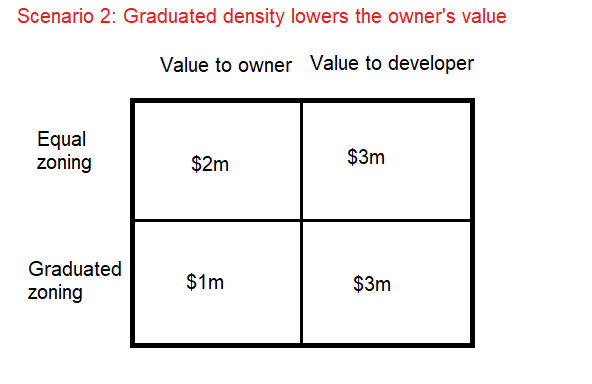

A case that Shoup doesn’t explicitly discuss is Scenario 2, where the small lot owner could gain some value from the more-intensive zoning, but is blocked by the graduated density provision.

The owner and the developer are still playing the same bargaining game in Scenario 2, but regulations have contrived to make the “pie” they’re splitting larger than it would be under equal zoning and to worsen the owner’s bargaining position.

There’s only a plausible role for government here if you believe that the bigger pie & worse bargaining position will make deals more likely. But even then, you have to overcome a serious moral question of whether the government should put its finger on the scales in a bargaining game. And you ought to be quite certain that a lot more assembly deals will take place, because the new regulations seriously decrease the potential unassembled value creation.

No (that’s my answer to the post’s title)

The value of treating everyone equally under law is sufficient for me to be opposed to graduated density zoning. But even for unobjectionable policies, the changing nature of “efficiency” along even such a simple dimension should be cause for greater humility.

Photo: Salim Furth