Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern’s book Homelessness is a Housing Problem filled such a useful niche that even before I read it, I had started referring to it by acronym. But, like Missing Middle Housing, this book moved my priors in the opposite direction than the authors intended.

As a pro-housing person, I’m predisposed to find new reasons to love HIAHP (you can read my version of the “housing theory of everything” on Discourse). But I came away thinking that housing is very useful for preventing homelessness while not necessarily a solution to the penumbra of problems surrounding it: mental illness, drug abuse, public disorder, and so on.

Also read: Michael Lewyn’s earlier review in this space.

HIAHP’s strengths

Homelessness is a Housing Problem is structured around a series of graphs showing all the things that fail to explain regional variation in homelessness. These aren’t formal statistical tests, and of course it’s possible for relationships like these to reverse themselves in the presence of confounding factors, but the overall picture is nonetheless convincing: homelessness isn’t just an outgrowth of the broader social problems we associate with it.

The other great strength of HIAHP is its accessibility: aside from the second half of Chapter 1, which lays out their methodology, the authors keep everything at a ninth-grade reading level. This isn’t, and isn’t intended to be, a book for scholars, and you can give a copy to your aunt or your mayor and not worry that they’ll get bored or confused.

HIAHP’s weaknesses

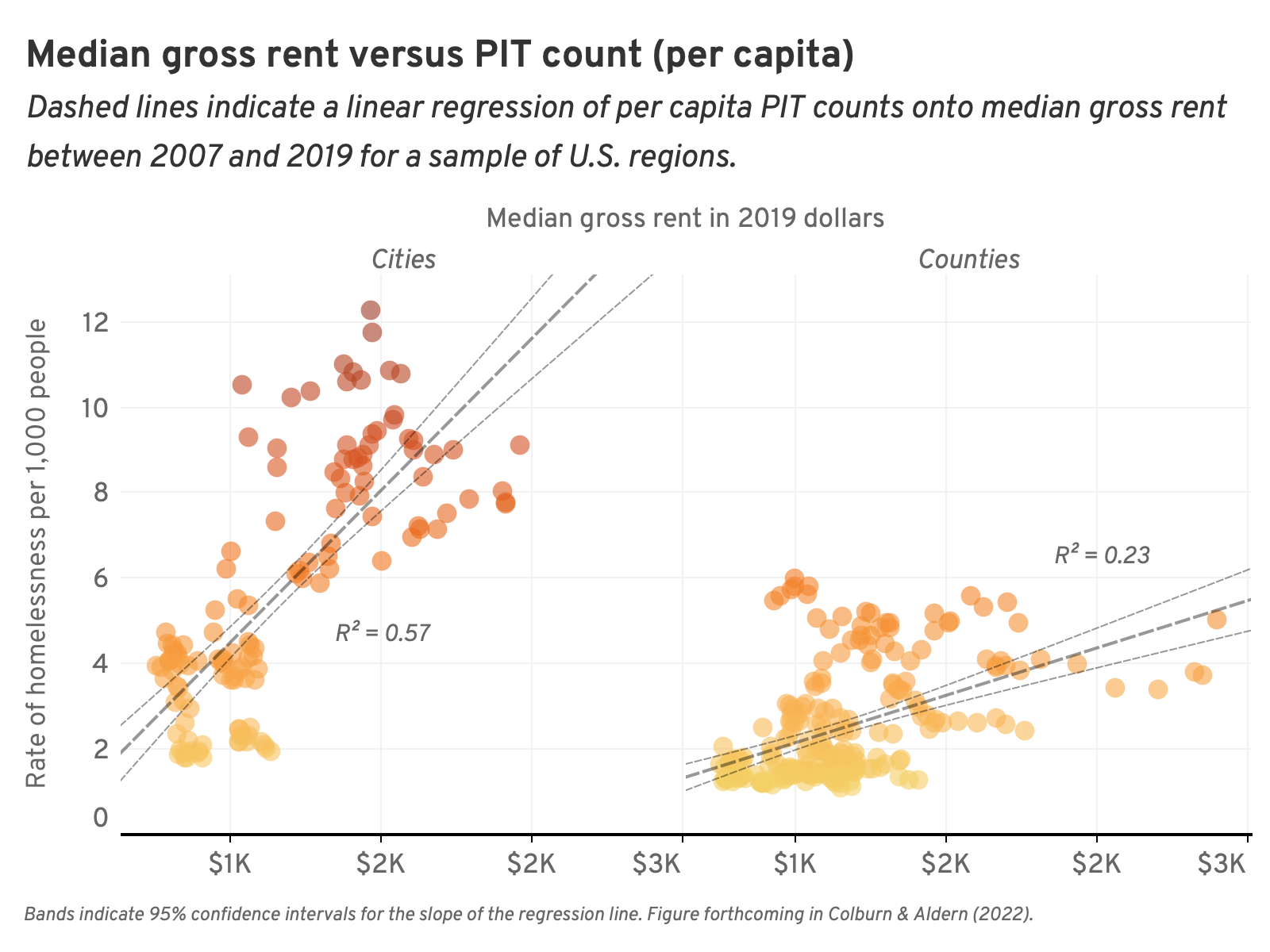

Against this parade of failed explanations, the authors present a powerful-looking graph of a clear positive relationship between housing costs and the rate of homelessness.

Colburn and Aldern’s simple graphs are persuasive in the negative. But positive proof requires more than a positive correlation – indeed, more than statistics alone. And it certainly requires correctly-executed statistics. Look again at the chart: instead of giving each city and county one data point, each gets 13. They differ slightly (2007 rent versus 2007 PIT count, and so on), but only slightly – they are strongly autocorrelated. Statistically, one would need to cluster the standard errors. (I emailed Colburn to ask about this problem and asked for his data; he did not respond.)

So those skinny error bands in the plots? They’re wrong. (The slope and R squared may be fine, though.) The whole relationship is much less certain than the authors claim. It’s very easy to imagine confounding omitted variables that might explain away the correlation via some intermediate factor or third cause. I shouldn’t need to say this, but correlation isn’t causation.

My disappointments ran beyond the statistics, though. I had hoped to learn from HIAHP the personal, micro-level narratives that links high housing costs to homelessness. Even in cheap cities, low-end rent isn’t so low that people without a regular income can afford an apartment of their own.

Are marginally-housed people in Birmingham and Buffalo renting rooms? Staying for free with family members? As Alexander the Grate said, everyone has “some degree of shelter insecurity”; it’s not a binary condition. There’s a huge liminal range between “leaseholder” and “homeless”; there must be cross-sectional differences in that range that explain why Buffalo can house people who Boston can’t.

HIAHP could have been a persuasive, useful addition to the literature either as a solid statistical work or as a qualitative exploration of the mechanisms linking market prices to homelessness. It falls well short of both.

Solutions?

The authors toss out some favored ideas for addressing homelessness. But without a micro-level understanding of low-end housing in cheap cities, it’s hard to evaluate these ideas.

Nor do the authors subject their suggested solutions, like expanding the portion of the housing stock “decouple[d] from the market”, to even the simple correlation tests that they used in the diagnostic part of the book. It’s plausible, given their diagnosis, that non-market housing is a major part of the cure. But it’s not obvious, nor is it a novel idea, and testing the performance of that idea would seem in keeping with the book’s approach.

In fairness, a market-only approach is equally suspect. The authors claim that “housing doesn’t magically ‘filter’ or trickle down to low-income households” (p. 134). Aside from the “magically” part, this is exactly what happens in a well-functioning housing market! It would be interesting to look at the residences of marginally-housed people in low-homelessness cities: I’d wager that more of them live in structures that were originally built to serve the top 1/3 of the market than originally “de-commodified”. But that’s a guess – I don’t know. More and better research is apparently needed to take us beyond solutions to homelessness with the epistemic status of a blog post.