In a pair of posts, Scott Alexander goads his mostly-YIMBY readers by claiming to believe that density is likely to increase prices.

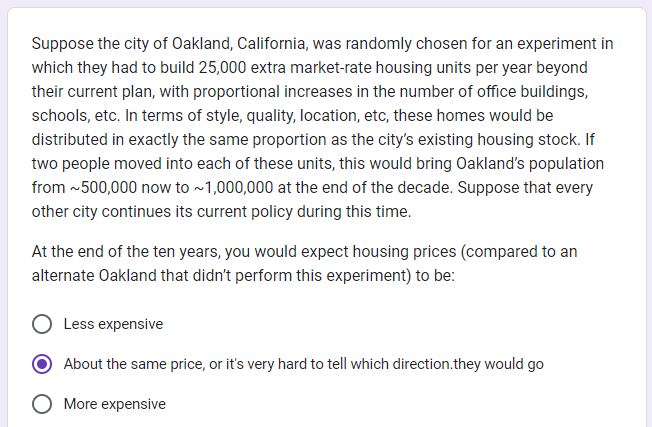

To quantify his readers’ views, he laid out a thought experiment in a Google poll, the results of which we’ll no doubt see in a few days. You can see the poll – and my answer – below.

As a YIMBY scholar, I mood-affiliate with the first answer, but I chose the middle one because there is a fundamental misunderstanding between pro-housing people like me and Scott’s recent posts.

Housing growth is not the same as city densification

Scott’s experiment isn’t a “housing growth” experiment, it’s a “city densification” experiment. Crucially, he requires “proportional increases in the number of office buildings, schools, etc”. That is, the experiment would increase office space at the same pace as housing even though office vacancy rates (19%) are far higher than housing vacancy rates (~1.7%).

Oakland is a pretty balanced city: as best I can tell from simple Census data, it probably has a jobs/residents ratio pretty close to the California average (by contrast, San Francisco has twice the state jobs/resident ratio). If Scott ran his experiment in a bedroom community, or stipulated that office space is left under current regulations, I’d have an easy time coming down on the “less expensive” side of the ledger.

The point of the YIMBY movement is that housing faces uniquely strict regulation. California cities (and those in some other states) believe that offices and industrial uses are “taxpayers”, generating more revenue than they use in services. Housing is viewed as a fiscal cost. Regulation (“fiscal zoning“) and discretionary decisions have reflected this bias for decades. The result is headlines like “SF added jobs eight times faster than housing since 2010.”

If Oakland upzoned citywide, it would likely receive a disproportionate amount of residential growth relative to offices and industry. That would lower rents relative to the baseline trajectory.

Scott’s question feels slippery because at first it sounds like he’s asking, “what would happen if we built a lot of housing?”, but in the details he’s asking, “what would happen if this city densified without changing any proportions.”

Thought experiments

The second, detailed question doesn’t neatly correspond to a simple comparative statics exercise in an Alonso-Mills-Muth city model. Depending on a variety of things like the congestion elasticity, people’s taste/distaste for density, and the degree to which regulation has held back density in the baseline, the price effects could go either way.

(If I had to try to run this experiment through an

Alonso-Mills-Muth model, I’d do it by imposing citywide regulation, removing the regulation for a section of the city, but also exogenously increasing the city wage. The first effect lowers prices, the second raises prices, and there are some externalities that are even trickier to think about. It’s a firm case of “too much going on here, we can’t give you an answer”).

There are some easier questions that urban economics models are well-equipped to answer:

- Are large cities cheaper or more expensive than small cities?

- More expensive. The only way they get bigger is by having higher wages or more amenities. That draws in greater demand, with prices at the exurban fringe being nearly equal everywhere, and then prices growing the closer to downtown you go. By the same logic, denser areas are dense because they’re more expensive, not vice versa.

- This is roughly the same logic as “Do people get wetter on days they carry umbrellas?”

- What happens to prices when a city removes housing density regulation?

- Housing prices fall, the population grows, and housing space per person rises.