“Wow!” the reporter said, “I knew you from Milton, but I didn’t know you were from East Milton. Tell me what it feels like?”

Well, until last week it was not that dramatic. East Milton is an old railroad-commuter neighborhood favored by affluent Boston Irish. It’s separated from the City of Boston by the Neponset River estuary and from the rest of Milton by a sunken interstate highway that makes it more congested and big-city than the rest of town.

MBTA Communities

In January 2021, Massachusetts passed the first transit-oriented upzoning law of the YIMBY era, now called “MBTA Communities,” “MTBA-C”, or “Section 3A”. Implementing regulations assigned a multifamily zoning capacity to each town.

Milton was always going to be one of the toughest cases for MBTA Communities. The northern edge of town is served by the Mattapan Trolley, which John Adams rode to the Boston Tea Party links up to the Red Line at Ashmont. The trolley makes Milton a “rapid transit community”, which means it has to zone for multifamily units equal to 25% of its housing stock. Among the dozen towns in the rapid transit category, Milton is the only one where less than a quarter of current housing units are multifamily; it also has few commercial areas to upzone.

East Milton dissents

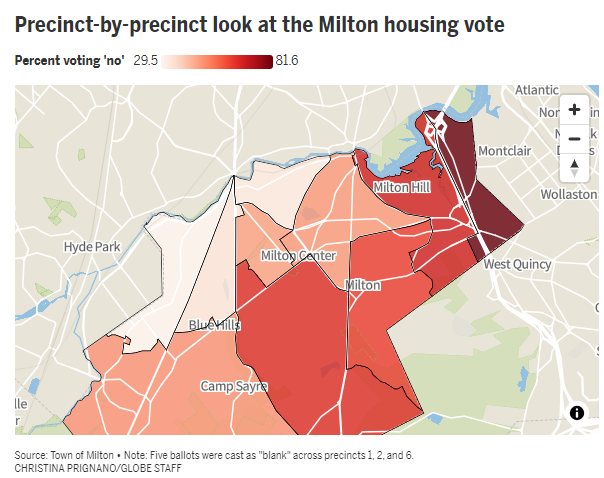

East Milton voters went to the polls on Wednesday and led a referendum rebuke of the plan. In Ward 7, it wasn’t close: 82% opposed the rezoning.

The Boston Globe offered a helpful breakdown of the surprisingly varied voting:

There are several hypotheses as to why the neighborhood went against rezoning so hard, all probably played a role.

- East Milton was assigned more than half the net new

multifamily zoning capacity despite lacking good transit access. - The neighborhood has been in a contentious, multiyear planning/suing process, so at least some residents were defensive and organized at the outset.

- It’s a very townie neighborhood. Growing up, I took it as a given that anybody who lived near me was Irish Catholic. Not being one myself, I didn’t quite belong. As a whole, the town is 16% Black, but East Milton is just rounding-error Black.

These reasons do not excuse East Milton. Its net multifamily zoning addition is so large because it has allowed so little multifamily housing in the past. The paucity of Black residents certainly suggests that prospective movers feel unwelcome.

Eliot Street YIMBYS

The real man-bites-dog story in Wednesday’s vote isn’t in East Milton. It’s along the street named for the Puritan apostle, which parallels the trolley tracks. The town’s plan (map, ordinance) put as much of the upzoning as possible into commercial or already-multifamily parcels. What was left was absorbed by Eliot Street and Blue Hills Parkway, plus some side streets.

The Neponset River in this section divides a 70% white census tract from a 95% non-white one surrounding Mattapan station. In my teen years, I remember a desultory movement to have the Capen Street trolley stop closed out of concern for crime. I expected these residents to vote no: theirs were the only houses being rezoned, and they live at the bleeding edge of a stark color and culture line.

The plan rezoned these single-family neighborhoods to allow 3 units per 7,500 square foot lot, up to 2.5 stories. Few, if any houses would be worth scraping, but some might be subdivided.

On Wednesday, the ward including Eliot Street voted 67%-33% in favor. The wards on each side of Blue Hills Parkway were also in favor. I don’t have a theory of the case. One person I spoke to pointed out that it’s a more progressive neighborhood. Another obvious aspect is that people here bought a home along a trolley line – they knew they were living in a city.

Who is the town?

Despite Eliot Street, “the town” failed to abide by MBTA-C. But who, exactly, failed? Is the town its staff? They worked exceptionally hard to comply. Is it the elected council, the Select Board? It complied. Or the representative town meeting members? They voted for the compliant plan 158-76.

But a state law allows voters to appeal the decision of a representative town meeting if they gather enough signatures. They did. In the resulting referendum, “the town” rejected “the town’s” decision.

Show me a hero, and I’ll write you a tragedy

I recently finished Lisa Belkin’s Show Me a Hero. You can take it as a tale about the racism or classism run amok, depending on which side you take. But I see it as a story about local democracy. The ruling in United States v. City of Yonkers didn’t just deconcentrate public housing, it also delegitimized a local democracy. The judge refused to make the hard decisions himself – he forced the city’s elected council to do so.

Whatever you may think of Milton, it is one of the world’s oldest continually-functioning democracies (362 years). It maintained its own militia and welfare system a century before the Declaration of Independence.

Democracies – local or sovereign – should not be omnipotent. Constitutional checks are vital at the top; hierarchical checks put guardrails around locals. Some areas of law are rightly outside local jurisdiction and the state can overrule a town.

But as Attorney General Andrea Campbell decides how to punish Milton for its failure to comply, she should keep in mind that no individual voter or representative should be forced to change his vote. The town can be overruled, but its democracy should not be mocked.