Jane Jacobs wasn’t optimistic about the future of civilisation. ‘We show signs of rushing headlong into a Dark Age,’ she declares in Dark Age Ahead, her final book published in 2004. She evidences a breakdown in family and civic life, universities which focus more on credentialling than on actually imbuing knowledge in its participants, broken feedback mechanisms in government and business, and the abandonment of science in favour of ‘pseudo-scientific’ methods. Jacobs’ prose is, as always, rich, convincing and successful in making the reader see the importance of her claims. Yet the argument that we are spiralling into a new Dark Age, similar to that which followed the fall of the Roman Empire, is not quite complete and I remain unconvinced that the areas she identified point towards collapse as opposed to merely things we could, and should, work to improve.

Let us start with the idea that families are ‘rigged to fail,’ as she puts it in chapter two. Jacobs, urbanist at heart, cites ‘inhumanely long car commutes’ stemming from the disbanding of urban transit systems, rising housing costs, and a breakdown in ‘community resources’ – the result of increasingly low-dense forms of urban development – as a significant reason why families are now set up for failure. She suggests our days are filled with increasingly vacuous activities, leading to the rise of ‘sitcom families’ which ‘can and do fill isolated hours’ at the expense of ‘live friends.’ That phenomenon has now been replaced by the ‘smartphone family’ where time spent on TikTok, and consuming other forms of digital media have supplanted the ‘sitcom’ family of the past. There has been significant literature on the detrimental effects of digital technologies to our physical and mental health, not least in Jonathan Haidt’s most recent book, The Anxious Generation. A similar picture is painted by Timothy Carney in his book Alienated America, where drawing on both his travels throughout the United States and on significant empirical data, Carney shows how significant parts of the United States have witnessed a complete breakdown in community and civic life over the past several decades. And yet – it is not clear that all of this points to a catastrophic ‘decline’ in civilisation as Jacobs puts it. We are fortunate to live in a country where there continue to be dynamic pockets of civic and social engagement. One might look at New York City, the suburbs of Washington D.C., or even the communities of Upstate New York, which I was recently fortunate enough to visit during a friend’s wedding, to see that there continue to be exceptions. This should lead to hope and optimism, for it suggests that whilst there are very real problems, so too do we have the tools to solve them and areas from which to draw inspiration. We could, and should, work to ensure our cities permit mobility, create the dense, lively and liveable neighbourhoods so brilliantly described by Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and encourage civic life by creating spaces instrumental to these activities. Yet so too should we recognise that different patterns for this exist, including in suburbs like Arlington and beyond. That diversity does not mean we are doomed for failure – quite the opposite as it can be seen as a form of experimentation and pluralism of values.

Now let us turn to the idea that our universities focus primarily on ‘credentialing’ rather than ‘educating’ – that higher education is now pursued primarily as a status symbol as opposed to for the inherent value it imparts to its participants. As a rising senior at Columbia University, one of these elite institutions, anecdotal evidence may be relevant here: there is definitely a pressure to excel in one’s GPA and secure the best grades possible, even to the detriment of actually learning. I have observed, amongst friends and coursemates, a tendency to pick classes that are easier and where teachers grade more nicely purely because of how it will look when applying to grad school and other professional endeavours. This is, in part, the price of a move towards meritocracy where individuals are (in theory) assessed on talent rather than on their connections or class and which therefore requires ever-more standardised measurements of individual success. Yet at the same time, coming to the United States has revealed that there exists a flourishing realm of liberal arts colleges and institutions that aim to go beyond pure credentialling and that do value education for its own sake. Hillsdale, Amherst and Middlebury are excellent examples of this. The pressure to attend elite schools goes beyond the status; these places are genuinely filled with some of the smartest and brightest people I have met, both from a faculty and student perspective. Jacobs is right to warn about the danger of higher education being sold to students as a ticket to some ‘elite’ strata of society, particularly given the significant expense and debt that students incur. And indeed university is not the right path for everyone, research has shown that other factors make a lot more difference to one’s professional success. Whilst Jacobs’ warnings are therefore valid, the issue is less acute in the United States where there is a significant financial reason to select a major and school that will impart actual knowledge and more of a problem in the United Kingdom and in Europe where subsidised higher education does mean that without a college degree, one will face significant difficulties in securing a position afterwards.

In the remaining portions of Dark Age Ahead, Jacobs identifies several other areas in very real need of reform, from the breakdown in self-policing of business and government to the abandonment of the scientific technique in areas like ‘traffic management.’ Her examples are vivid and teach the reader something, but they again fail to point to a wholesale breakdown in society as it is today. Most significant, however, is Jacobs’ analysis of the ‘dysfunctional’ financial arrangements of local and national governments which expand on Cities and the Wealth of Nations. National governments, in their current form, have a set of incentives at cross-purposes with how economies actually grow. By funnelling money away from cities and into ‘dead-end’ economic causes – in effect dispensing largesse – governments detract from the ability of individuals and firms within those cities to reinvest, innovate and find ever-more ingenious ways of ‘adding new work to old.’ Welfare, subsidies, and redistribution cannot drive a civilisation’s success. Only innovation and progress can, and if current trends persist, we may spiral into decline.

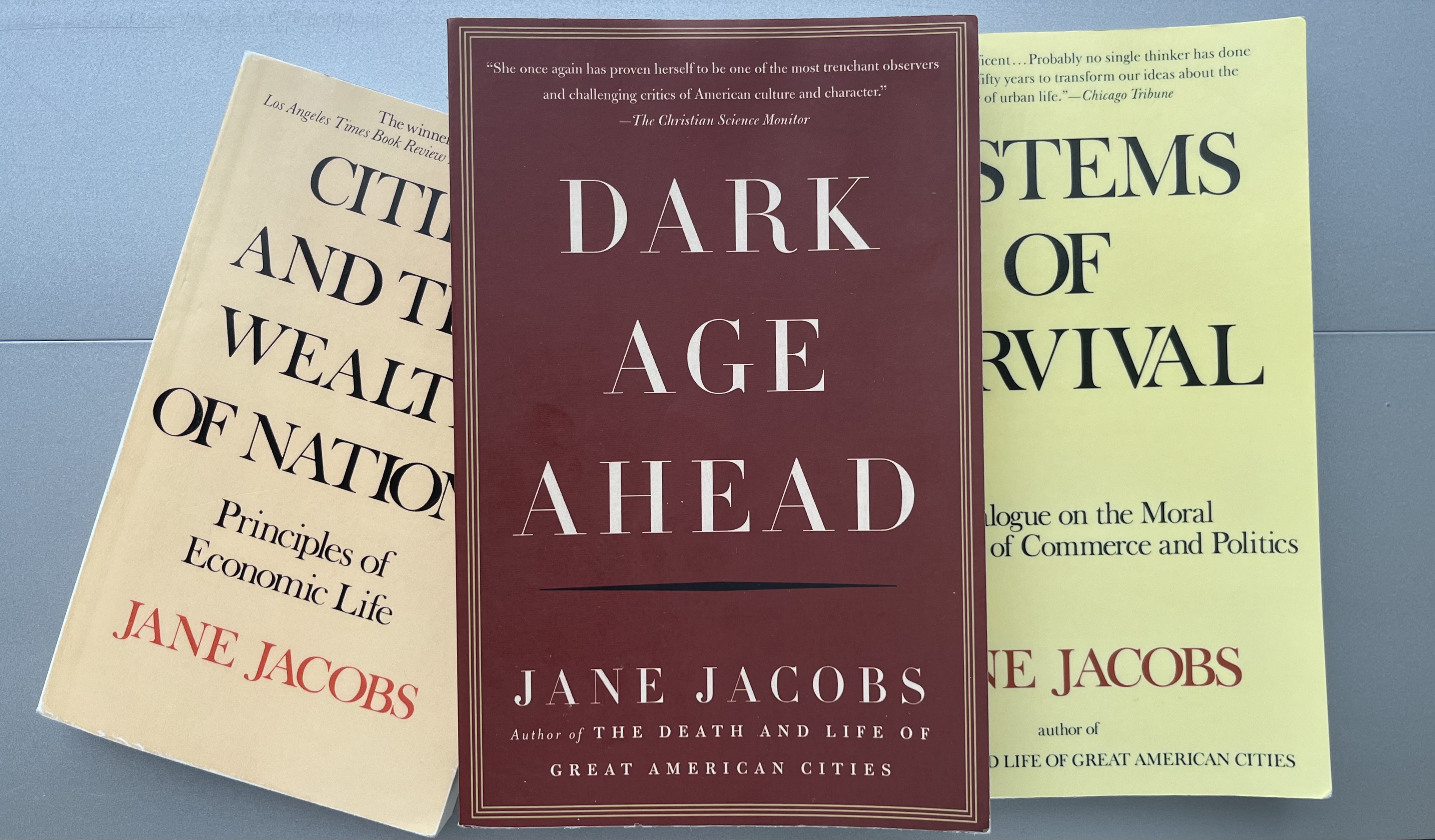

Where Dark Age Ahead excels in its analysis of the historical and theoretical concept of Dark Ages. The book ought to be read more for its historical analysis and its applicability to political economy and economics, than for its analysis of the contemporary issues identified, for as important as these are, more recent and accurate analyses can be found in Jacobs’ other books and those of other scholars. This book underscores the importance of not taking our institutions for granted, of promoting entrepreneurship and innovation so as to move ahead, and of constantly revisiting the Great Thinkers from the past.

In conclusion, Dark Age Ahead contains some real golden nuggets and makes for a compelling read for those wanting to understand the historical dynamics of dark ages and some of the dangers we currently face. Yet for the reader unaccustomed to the work of Jane Jacobs, I would instead suggest reading The Economy of Cities, which better urges one to rethink where growth happens and why cities are the driving force of civilisation.